Dear Tatiana and Mike

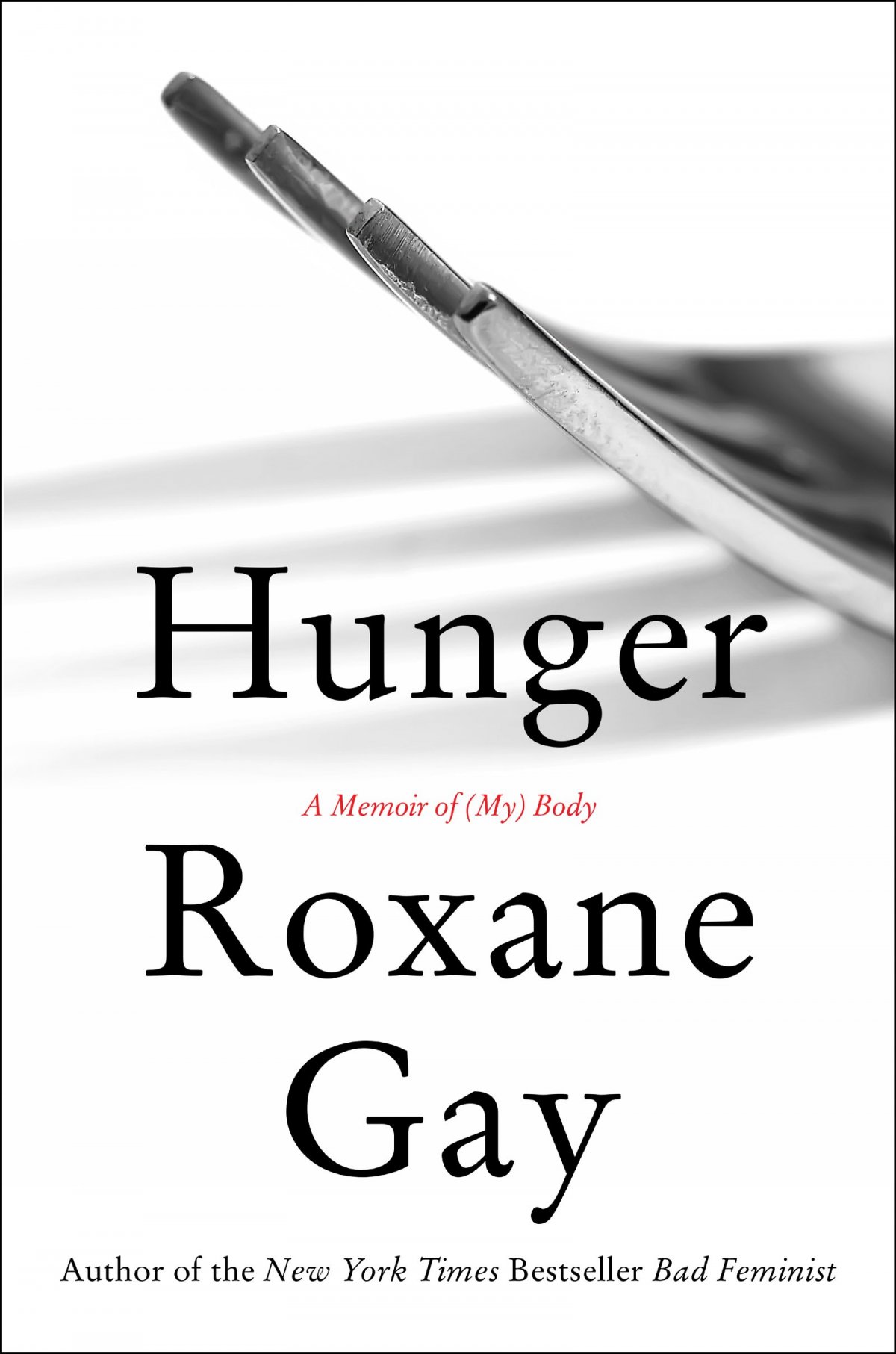

Hunger is probably one of the most heart-wrenching and powerful memoirs I have ever read. Written by Roxane Gay, the author of Difficult Women, Hunger is a personal and harrowing tale that details her struggle with weight and how it has impacted her childhood, teens, and twenties. In the beginning, she opens up with the struggle of dealing with her “wildly undisciplined” body and how she claims she is “trapped in in a cage” (Gay 17) because of the rape she suffered when she was twelve years old. So, she turned to food as a comfort, gaining more and more weight because “[If] I [Gay] felt undesirable, then I could keep more hurt away” (Gay 15). I felt a strong sense of understanding with this topic. I don’t know about you guys, but while I’ve never struggled with my weight, I know first hand about what trauma can do and how it can decimate a person until they are nothing. You feel like nothing, so you treat yourself like you are nothing because that’s what you feel what you deserve.

I liked how straight-forward and honest she was about the content of her memoir, stating that “This is not a weight-loss memoir. There will be no picture of a thin version of me, my slender body emblazoned across this book’s cover…Mine is not a success story. Mine is, simply, a true story” (Gay 4). I find myself admiring her cutthroat approach of warning the reader that not every book will have happy endings. Life is full of hardships; most things will inevitably get worse before they gets better, until you reach a place in your life to balance out the bad and the semi-good things that come across your life.

I look forward to hearing from the both of you soon,

Tiara

–

Dear Tiara and Mike,

I also found Hunger to be a very well written and powerful memoir. This novel really helped me to understand Gay’s struggles in ways I never would have imagined. Gay’s trauma plays a very large role in her struggle with her body, and in a way this memoir puts you into her body and makes you feel all of her imperfections. Like Tiara I also felt as if I could better understand her point of view when Gay went into detail about her trauma. She looks at her body as a constant physical reminder of the trauma she endured: “The past is written on my [Gay’s] body. I carry it every single day,” (Gay 41). Through all of this, she also struggles to fully tell her story for the next 25 years and had chosen to keep this trauma a secret from everyone. However, now that she is in the state of mind to be able to write this memoir she is also able to begin to unravel how she felt, and how this trauma has shaped her mind. “Those boys treated me [Gay] like nothing so I became nothing,” (Gay 45). This analogy works really well in that it paints a picture of what’s wrong with anti-feminist thinking. Girls’ bodies are viewed as objects that are only in existence to serve men. So, when you ingrain this into a twelve-year old girl’s brain that her assault is a result of her having a nice body, then it only makes sense that she would, in turn, choose to destroy it to avoid having to face that trauma again. However, it wasn’t until high school that she learned that “being raped wasn’t my [Gay’s] fault,” (Gay 71). Yet, even with this new possibility of healing we see that Gay doesn’t see herself being able to truly heal.

Gay’s trauma being a key factor for her weight gain is very in tune with current social issues. I think that is what made this novel so successful: it’s urgency with a topic so prevalent. She cites many examples of how she is discriminated in the American culture because she is overweight. We see the importance of understanding mental illness in today’s society. Without understanding Gay’s mental struggles over most of her life we wouldn’t really be able to see how that has shaped who she is. Without this back story all we see is a woman who became medically overweight, but once we have the trauma we understand that she is a woman who is a victim of rape culture. Eating was Gay’s coping mechanism and not a result of being lazy. In a world where girls are told to dress more conservatively to avoid harassment from boys, Gay’s adolescent self took that one step further and changed her body to protect herself.

One thing I noticed that was very prominent in this section was that Gay tip-toed around the subject of her trauma before diving in with details. This left me feeling somewhat confused because for a while I didn’t think she was ready to acknowledge that part of her life. With this being such a sore subject, I began to wonder if the trauma was too painful for her to write about. However, then she dove in and that part felt somewhat abrupt to me. The writing leading up to the story didn’t seem to flow very well into it. Once she had actually gotten into the story I feel that the writing became more comfortable and all of her ideas began to reconnect.

I look forward to your thoughts,

Tatiana

–

Dear Mike and Tatiana,

Following up with Tatiana’s statements, Gay elaborates how, while she is the cause for her weight gain, she does not agree with the extreme health and beauty standards that America has adopted. Obesity is not only looked down upon in America, but in several different cultures as well. Gay is Haitian-American and in her heritage and household, being overweight becomes a huge concern. She states, “when you are overweight in a Haitian family, your body is a family concern” (Gay 55), mostly, as she also explains, is the fact that they associate being overweight with being gluttonous. As some of you may know, Haiti is (sadly) mostly known for being underdeveloped and poverty stricken. Though this is just a common stereotype, people only have an outside point of view. However, because of the psychological trauma she suffered as a result of her rape, she is never successful in keeping the weight off for long. Both cultures have a very negative outlook on individuals who are overweight, and while not all people think that way, the media portrays it as such.

This is very disheartening because not every person that is considered “skinny” is not always considered healthy, and not every person who is considered “fat” is not always unhealthy. I have a family member who is constantly struggling with her weight because of her battles with depression and bipolar disorder. Because of this, she has adopted unhealthy eating habits, finding comfort in the one thing that continues to impact her negatively until this date. She also suffers from a number of different health complications like diabetes and sleep apnea. It can be frustrating to see how unhappy she is because of the way she looks. I don’t know about you guys, but it’s hurtful to watch the ones you love destroy themselves from the inside-out. It can be frustrating to see how unhappy they are because of the way they look. As I got older, I realized that the way you see yourself is all about perception and the cultural values which can impact those that do not fit within the norms. The terms “skinny” and “fat” have both become so skewed by society that many people grow up not ever being fully comfortable with themselves because the definitions of the terms change so frequently, even though the human body cannot.

Let’s talk about this some more in our next correspondence,

Tiara

–

Dear Tatiana and Tiara,

I hope you both appreciate that I actually had to get out of bed to make coffee in order to write this and have it make sense. I was not coherent about 10 minutes ago.

You two have raise quite a few points about the struggles that this young woman faces with her introduction into American society. The literature is insightful into a very real situation that exists, especially in America. People who visit from foreign countries may be taken off guard with the harsh body standards that are present here. This is not to say that Haitians don’t like to eat, but they have a different societal expectation. In fact, “Haitians love the food from our island, but they judge gluttony” (Gay 55). In America, gluttony is not such a publicly shameful thing, but being raised with different values has effects on people. Gay is one such example where her perception of body image was thrown off with the negative outlook she started to have about herself when she learned how the terms “fat” and “skinny” were used so extremely. Though she suffered with these standards, she also gained insight into how Americans differ from other countries’ populations and how people view themselves.

The fact that we mention that the author appears to tip toe around the recollection of past events in her life is an interesting prospect. One would beg the question as to why this might be the case. A few suggestions came to mind after reminding me what I had read. Gay could be nervous about remembering what had occurred in her life, not wanting to have to recall the traumatic experiences and the feelings associated with them. Another possibility is that she aimed to entice the reader to keep reading the work and to gain more interest as time goes on. It could be as simple as a marketing ploy, but most would tend not to think this way. There are multiple interpretations that one could develop by journeying through this memoir. Perhaps one of you could offer some insight into her struggle with her body.

Best,

Mike

–

Dear Tiara and Mike,

To further dive into what Mike was working through on Gay’s struggle, I feel that Gay makes a point to say that the struggle she faces with her body is even more complicated by the shame she feels. Fat-shaming becomes an ever-present problem for her in her daily life, which we see when she says, “When I am walking down the street, men lean out their car windows and shout vulgar things at me about my body, how they see it, and how it upsets them that I am not catering to their gaze,” (Gay 188). She explains that this creates a conflicting environment for her (Gay 199). There is shame in the fact that she would have an eating disorder as a fat girl. She tells us that people are more likely to support correcting an eating disorder.

I think Gay hits the mark with another major social issue within this section, which I think only strengthens her writing. The last few years have been dedicated to focusing on body positivity. We see actors and singers like Demi Lovato who suffered with eating disorders as well as bipolar disorder. We also see actors like Jennifer Lawrence who worked to be a strong female lead that looks healthy instead of too skinny. We’ve even seen some countries like France ban the use of models that look too underweight from modeling as well as an increase in the amount of “plus-size” modeling included in magazines. The world is trying to move to a place that eradicates shame for being bigger. However, we still tend to really only focus on eating disorders where the person is only becoming too skinny. If they’re already fat, we don’t really see it as an issue, but rather as a solution. This is what Gay made a point of when explaining her own struggle with eating disorders. She suffered from bulimia, but she never got to the point where she was skin and bones. Her body remained “imperfect.” Using this point of view on eating disorders helps us to see why Gay struggled so much in truly being able to come to terms and accept that she had an actual eating disorder that needed medical attention. She let it go on because she knew society didn’t see it as that big of an issue.

Warm regards,

Tatiana

–

Dear Tiara and Tatiana:

As I eat my incredibly unhealthy fast food, I am writing about eating disorder, which is ironic to say the least. I have a McChicken and some fries to be exact.

Eating disorders are another major concern that many people have sensitivity to. It would be best that we stride carefully when referring to these concerns. It looks like we are doing just fine at this point, which is great. The eating disorder that Gay faces in this book is a detail that could stand for a little more detail. That being said, I would propose the question of when Gay originally became aware of the eating disorder. The issues could stem from the manner in which she was raised and the values that she was raised by. She may not have been considered to have an eating disorder until certain people came across her and decided as such. Gay’s journey back through her younger years is as much of a recollection as it is a way for her to see how much outsiders influenced how she felt about herself.

Body positivity is another movement that we can appreciate throughout this book. People are typically supported when they decide to change their eating habits, but in a healthy manner. This memoir shows this by sharing how she “became vegetarian because [she] needed a way of ordering [her] eating that was less harmful” (Gay 199). Gay went through her situation at a time before the body positivity movement was blown up as it is today. However, one could note that body image problems have always been present among woman and men, and especially focused in America. Only recently has it grown enough to sincerely be supportive. This is a good theme from the book: addressing body image concerns.

From the warmth of my bed,

Mike

***

Afterword from the Writers

Roxane Gay’s Hunger focuses on immediate social issues of body image. The book was written as a memoir to her body and she does something out of the box by using her body as a vessel to truly represent these issues. She brings to light issues such as stereotyping, mental health, eating disorders, and fat shaming all by using her own experiences. In these experiences we see firsthand that these issues are very real and in turn can have a depreciating effect on the human body.

About the Author: Roxane Gay’s writing appears in Best American Mystery Stories 2014, Best American Short Stories 2012, Best Sex Writing 2012, A Public Space, McSweeney’s, Tin House, Oxford American, American Short Fiction, Virginia Quarterly Review, and many others. She is a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times. She is the author of the books Ayiti, An Untamed State, the New York Times bestselling Bad Feminist, the nationally bestselling Difficult Women and the New York Times bestselling Hunger. She is also the author of World of Wakanda for Marvel. She has several books forthcoming and is also at work on television and film projects.

About the Author: Roxane Gay’s writing appears in Best American Mystery Stories 2014, Best American Short Stories 2012, Best Sex Writing 2012, A Public Space, McSweeney’s, Tin House, Oxford American, American Short Fiction, Virginia Quarterly Review, and many others. She is a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times. She is the author of the books Ayiti, An Untamed State, the New York Times bestselling Bad Feminist, the nationally bestselling Difficult Women and the New York Times bestselling Hunger. She is also the author of World of Wakanda for Marvel. She has several books forthcoming and is also at work on television and film projects.

About the Authors of this Post: Tiara Hawkins is a junior majoring in English with a writing emphasis. She enjoys reading and sleeping when she is not working or going to school. She works as a reader and operates the Facebook and Tumblr page for 30 N.

Michael Larrea, on his last term at North Central College, is majoring in Information Technology. His knowledge of how to make equipment work really helps with events that 30 North has wanted to host this year. He is forward thinking and expressive with his ideas.

Tatiana Guerrero is a senior at North Central College pursuing an English writing degree. She loves curling up on the couch with a good thriller novel and a hot cup of coffee. After graduation she hopes to pursue a career in publishing.

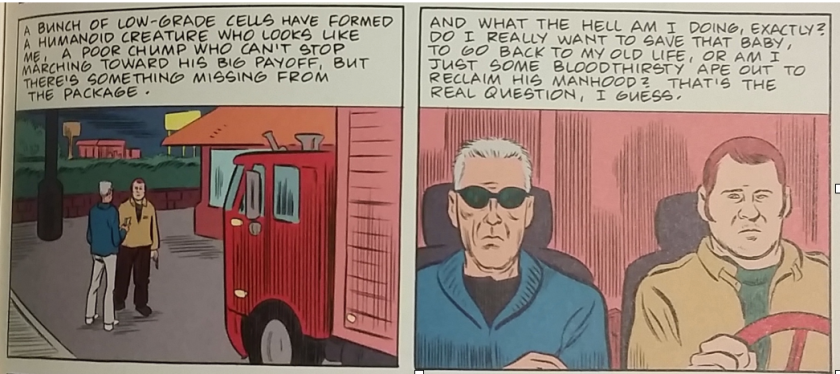

About the Author: Daniel Clowes was born in Chicago, Illinois, and completed his BFA at the Pratt Institute in New York. He started publishing professionally in 1985, when he debuted his first comic-book series “Lloyd Llewellyn.” He has been the recipient of multiple awards for his seminal comic-book series, “Eightball.” Since the completion of “Eightball” in 2004, Clowes’ comics, graphic novel, and anthologies have been the subject of various international exhibitions. Clowes currently lives in Oakland, California with his wife and son, and their beagle.

About the Author: Daniel Clowes was born in Chicago, Illinois, and completed his BFA at the Pratt Institute in New York. He started publishing professionally in 1985, when he debuted his first comic-book series “Lloyd Llewellyn.” He has been the recipient of multiple awards for his seminal comic-book series, “Eightball.” Since the completion of “Eightball” in 2004, Clowes’ comics, graphic novel, and anthologies have been the subject of various international exhibitions. Clowes currently lives in Oakland, California with his wife and son, and their beagle.

About the Author: Sandra Simonds’ poems have been included in the Best American Poetry consecutively in 2014 and 2015, and have appeared in many literary journals. She is an Associate professor of English and Humanities at Thomas University in Georgia, and lives in Tallahassee, Florida.

About the Author: Sandra Simonds’ poems have been included in the Best American Poetry consecutively in 2014 and 2015, and have appeared in many literary journals. She is an Associate professor of English and Humanities at Thomas University in Georgia, and lives in Tallahassee, Florida.

About the Author: Solmaz Sharif was born in Istanbul to Iranian parents. She holds a degree from U.C. Berkeley, where she was a part of Poetry for the People, and from New York University. In 2014, she was selected to receive a Rona Jafe Foundation Writer’s Award. “LOOK” was a finalist for the National Book Award. Her works have appeared in The New Republic, Poetry, The Kenyon Review, jubilat, Gulf Coast, Boston Review, Witness, and various others.

About the Author: Solmaz Sharif was born in Istanbul to Iranian parents. She holds a degree from U.C. Berkeley, where she was a part of Poetry for the People, and from New York University. In 2014, she was selected to receive a Rona Jafe Foundation Writer’s Award. “LOOK” was a finalist for the National Book Award. Her works have appeared in The New Republic, Poetry, The Kenyon Review, jubilat, Gulf Coast, Boston Review, Witness, and various others.

About the Author: Laura van den Berg was raised in Florida and earned her MFA at Emerson College. Find Me is her first novel, which was selected as a “Best Book of 2015” by NPR, Time Out New York, Buzzfeed, and others.

About the Author: Laura van den Berg was raised in Florida and earned her MFA at Emerson College. Find Me is her first novel, which was selected as a “Best Book of 2015” by NPR, Time Out New York, Buzzfeed, and others.

About the Author: George Saunders was born in Amarillo, Texas, but grew up in Chicago. He completed a degree in exploration geophysics from the Colorado School of Mines. He later completed his MFA from Syracuse, where he also met his future wife, Paula Redick. Saunders has had various works published in The New Yorker and Harper’s Magazine.

About the Author: George Saunders was born in Amarillo, Texas, but grew up in Chicago. He completed a degree in exploration geophysics from the Colorado School of Mines. He later completed his MFA from Syracuse, where he also met his future wife, Paula Redick. Saunders has had various works published in The New Yorker and Harper’s Magazine.

About the Author:

About the Author:

get your way, another example of intriguing work.

get your way, another example of intriguing work. About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author:

About the Author: